Superstorms and Wetlands

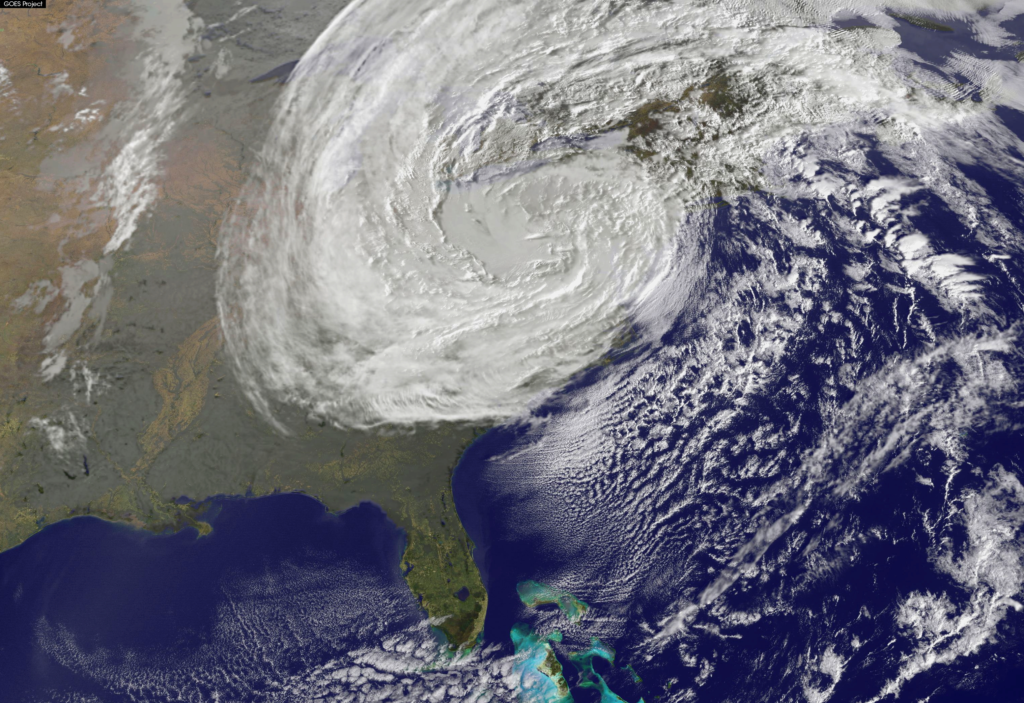

As we approach the 8th anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, it is time to remember and consider the impact the superstorm had on Staten Island and the rest of the city. NYC lost 43 people to Superstorm Sandy and half of those were Staten Islanders. Many homes were badly damaged or destroyed in Staten Island, The Rockaways, the New Jersey shore and on Long Island. Because we live on an island, New York City residents are vulnerable to the climactic and environmental conditions around us. The superstorm has motivated many of us to get a better understanding of the environment as well as how to preserve natural storm barriers so they may save homes and lives in future storms.

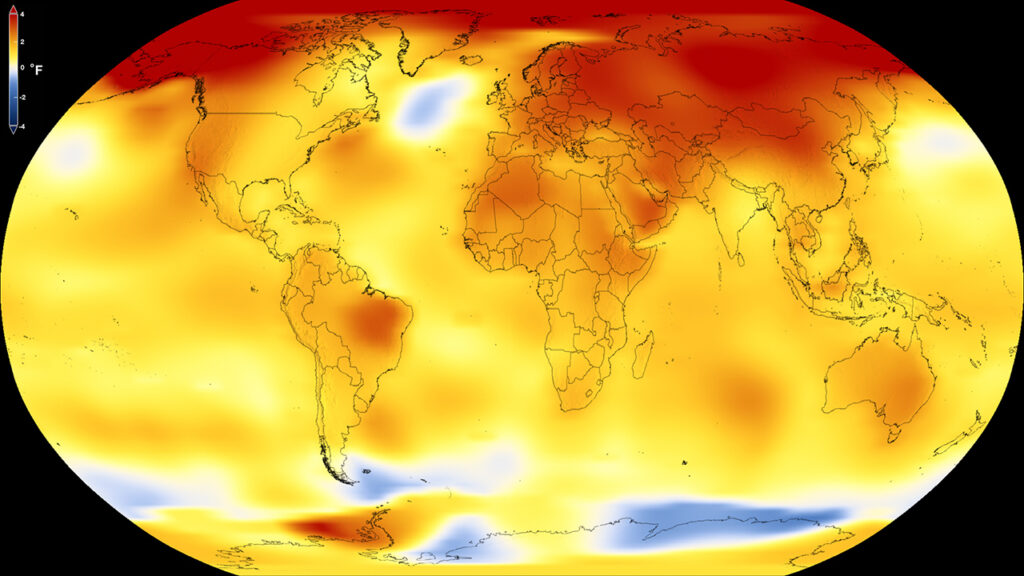

With the rising threat of climate change, storms are becoming more and more common and stronger. This year alone, as storms ravaged the Gulf Coast we officially ran through the whole alphabet of names for storms from A-Z. What is contributing to the increased frequency of storms and what is making them stronger? What can we do to help stop the damage and what already exists in our natural environment to help alleviate some of the damage from these storms?

With temperatures rising across the world, the seas are getting warmer causing the polar ice caps to melt at a faster pace, and a rise in sea level. This self-perpetuating loop is causing a higher frequency of storms and harsher storms than normal. The cooling and heating of oceans can have a big impact on the number of hurricanes that form each hurricane season, as well as how much damage they cause. Wind also plays a part, especially the wind patterns of El Nino and La Nina. With all of these factors in play, it is no surprise that storm formations across the world, from cyclones and typhoons, to hurricanes, are increasing in intensity.

These factors also led to the formation of Superstorm Sandy in the Atlantic Ocean back in 2012. NYC was heavily damaged by the storm surges, especially low-lying areas in lower Manhattan and Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Queens. Subway tunnels and stations were flooded with sea water, disrupting service for months, and MTA is still fixing the damage to the tunnels. Much of the NYC coastline was vulnerable because neglect and development had removed natural barriers. Areas of coastline where barriers, such as dunes and wetlands, were present experienced much less damage. For example, the area around Freshkills Park was spared, as the wetlands absorbed most of the storm surges and mitigated the rising water levels. We can learn a lot about mitigating storm impacts by looking more closely at wetlands.

A wetland is a unique and diverse ecosystem that is usually filled with water, either from ground water or from storms. A wetland can consist of variations of marshes, swamps, wet meadows and bogs. New York City is unique in that we have a variety of wetland ecosystems throughout the city, including those at Freshkills Park and Jamaica Bay. What makes a wetland different from a pond or a lake, is the rich plant and aquatic life in and around it. Wetlands play a crucial role in the ecosystem, by collecting and purifying water and supporting local and visiting wildlife. During a storm, wetlands can absorb the brunt force of a surge by absorbing the water and storing it, mitigating damage to homes and upland areas.

![]()

With the understanding of the significance of wetlands, wetlands preservation has gained momentum on Staten Island and throughout the country. Locally, Staten Island’s Bluebelt Program focuses on the preservation and enhancement of wetlands to manage storm water. The program began in the early 1990’s as Staten Island was experiencing an increase in flooding due to both weather and, as a result of development, the loss of permeable surfaces that allowed storm water infiltration. The program has also been implemented in other boroughs across NYC dealing with similar issues, including the Bronx and Queens. The Bluebelt includes structural and nonstructural storm water management control measures that help control the quantity and quality of storm water runoff. Nationally, states are also implementing their own policies and laws to help protect wetlands. In California, Governor Newsom penned a new law that will help protect 30% of lands across the state, including wetlands.

With a renewed understanding and appreciation of wetlands as well as their enhancement and preservation through programs like the Bluebelt Program, we hope to be better prepared to meet the challenges associated with climate change. To learn more about the Bluebelt, click here.