“City Squares” and Sharing Urban Space

How do we share a space? Further, how does a subjective relation to place and a relation to others map onto one another? The places in question here are urban, public spaces and exist, whether as an active choosing or unconsciously, in relation to another’s experience of a space. Our sense of geography need not be a private experience, an isolated contemplation, but may be shared, entangled in what is interpersonal.

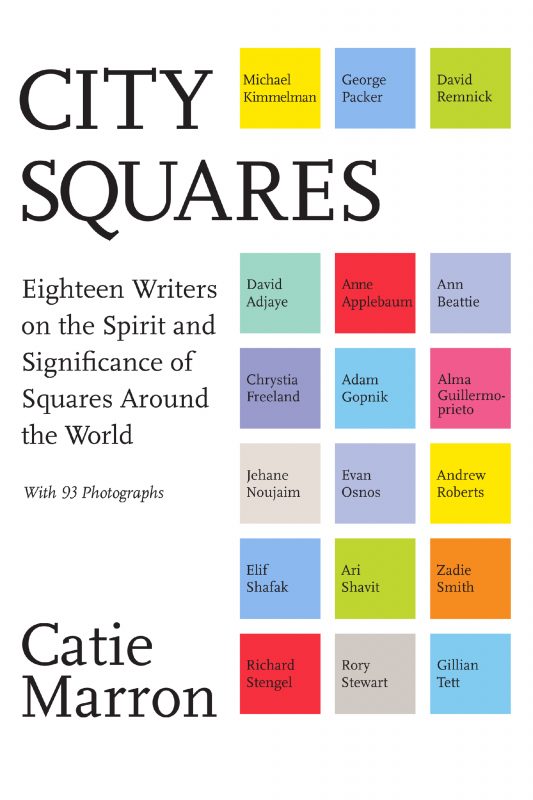

In Catie Marron’s new publication City Squares: Eighteen Writers on the Spirit and Significance of Squares Around the World (HarperCollins 2016), city squares are a point of departure, a way to answer the question of how we may come to share a space. Told through a collection of essays by 18 writers, from The New Yorker Editor David Remnick to contemporary author Zadie Smith, City Squares presents different facets of this particular type of urban space. Ranging from the personal and the geopolitical, cultural and architectural, Cape Town to Tel Aviv, the book itself functions as a public square as it presents a collection of voices.

The Architectural League, Rizzoli Bookstore, and HarperCollins recently hosted a conversation between Catie Marron; Michael Kimmelman, contributing essayist and New York Times architectural critic; and Reed Kroloff, architecture critic and educator, which described these public spaces, situating them in the era of the Bloomberg era: an era with an increased effort to pedestrianize New York City. One particular effort was converting unused traffic triangles into city squares, seen at the General Worth Square, adjacent to Madison Square Park and only blocks away from Rizzoli Bookstore where the conversation was held. There is a noticeable difference, Marron describes, as you walk from Madison Square Park into General Worth Square. Parks, she states, are a retreat, an idyllic daydream within urban life. At city squares, by contrast, you feel a certain “thereness,” a feeling that yes, I am at the center, I have found it. With this distinction, we have begun to pinpoint just what makes city squares what they are. It is these public spaces that New Yorkers have an “infinite appetite” for, an “insatiable demand,” in Kimmelman’s words.

City squares are made great by this ineffable sense of “thereness,” produced, interestingly enough, not through its “physical components” (Kimmelman), that is, the fact that it is square or round or features a genius architectural design. What, then, makes these squares what they are? Marron lists central location, the ability to develop over time, and human scale as key attributes. Kimmelman adds that they are organically linked to the neighborhood. Growing out of passages through to another part of a city, or at the end of a block, city squares can’t be plotted methodically. The sense of being in the midst of things that makes a city square really thrive, that give space its meaning, is found through its relation with people. This sense of “thereness” comes from being with others. Here, people come to replace architecture. Notice, for example, the difference felt in an urban space at noon and at midnight. In the afternoon, a busy urban square captivates us with different faces, narratives, uniquely different subjects that we encounter rather than the architectural design of the given space.

At the close of the talk, members of the audience were invited to name the city squares that they think of fondly. From San Francisco’s Washington Square Park, to Old Square in Stockholm, and the town square in Siena: different countries, memories, and pasts were invoked. Influenced by associations, moods, and inclinations, laden with secret histories, entwined with the present, and layered with the personal, these are places influenced by who we are and who we were with when they were experienced. These places are shared in the interpersonal, in the experience of and with others.

A multiplicity of individual bodies are contained within the shared and inhabited spaces of urbanism, a collective of embodied selves and their desires, imaginations, narratives, dreams, associations of ideas, and predilections. Yet, we are not trapped within our own experience of place. We come to share these places with others, reaching outside of ourselves to affirm our various connections to others. Think here of how people routinely share a space: at a transit stop, a library, a park or playground. At a public park, children fly kites during a breezy summer day and groups of teenagers play basketball. People go for runs, or walk their dogs. This space may also be a respite for some, as they sit in solitude on shady park benches. It may additionally be a social space, as parents chat in groups, or couples and friends meet up to enjoy the day. Public space meets different needs, various desires. We are aware, even if these thoughts do not take precedent, of the ways others use a space in ways that we may not. Sharing a space offers us the chance to reach across the divide of one’s own perception to respect another’s right to space.

Within shared spaces is a collective identification. Public squares become referents of our sociability and an engagement with others. They are a testament to our interconnected state of being in the world. A spatial commitment, founded through participation in and appropriation of a place, creates a mode of belonging. These multiple and shared geographies foster the spirit of the place. With difference creates community, an intimacy within publicity, a plurality and commonality with particularity. It is in this space that we hold ourselves accountable to others.

Written by Savannah Lust, Freshkills Park Development Intern