Pond Turtles

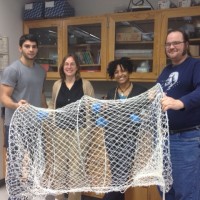

PhD researcher Seth Wollney with a snapping turtle from Freshkills Park

Since 2012, researchers from the College of Staten Island (CSI) have been studying the biodiversity of Freshkills Park’s ponds with a focus on painted turtles. This comparative study is looking at painted turtle populations in the park’s rainwater basins compared to three other populations around Staten Island.

When rainwater falls on Freshkills Park’s hills, it’s collected through a network of swales, channels, and downchutes, then sent to detention basins at the bottoms of the hills. This system ensures that water doesn’t destabilize or erode the layers of soil that make up the landfill cover. Since this engineering was installed, the quiet waters of the detention basins have become freshwater ecosystems that serve as a habitat for a variety of wildlife, including painted turtles.

According to PhD candidate Seth Wollney, the turtle research project involves a “capture-mark-recapture” program. The researchers catch the painted turtles, add unique markings to their shells and record the details, then release them back into the ponds. This allows them to keep track of individual turtles over time to inventory and assess the population health.

Since the program began, researchers have captured over 100 turtles in Freshkills Park, and they’ve observed stable populations in the park’s rainwater basins. “We’ve actually seen a lot of turtles stay and surviving quite well between seasons and between years,” Wollney said. “Comparative to other ponds around Staten Island, the populations at Freshkills are pretty healthy and they fare relatively well despite the fact that the habitat is really only around 20 years old.”

Wollney believes that studying turtles is important because they can act as indicator species, which means that they show the health of the ecosystem. “They are positioned somewhat higher up on the food web of the pond,” he explained, “and you need to have a healthy pond to sustain a healthy population of turtles.”

For Wollney, the big question that researchers are trying to ask with this project is whether a new population in a post-industrial landscape can be as healthy as populations in ponds that have been around for 40 to 120 years. “We’re studying one species,” he said, “but really the knowledge and the insights that we learn by studying one species can extrapolate outwards to help with either encouraging various wildlife to recolonize the park or to sustain and manage for the species we currently have at the park.”

Wollney also pointed out that turtles are one of the most threatened groups of vertebrate animals in the world right now, with over 30-50% of turtle species listed as threatened on The IUCN Red List. “Painted turtles are spread continent wide; they’re generalist species, and they are very common today,” he said. “But understanding the threats that they face under the constant encroachment of urbanization will help in the long term to keep what is ‘the common turtle’ common. Studies and research of different species of animals in urban contexts will help us learn the process to maintain higher levels of biodiversity for the long term.”

See more coverage on this research project on NY1.